_ force fit

tag: [work] [automavision] [phygital] [digi]

date: 20220525

classification: Capri 22 international workshop

location: Capri Italy

external link: archtectmagazine.com;

organizer: Aaron Betsky & Francesco Delogu

“The island of Capri exists as fairytale place of escape and hedonism, as well as a tourist site focusing on wealthy vacationers during a few months of summer. With a history that reaches back to Roman era, a landscape that has been terraformed to resemble Western ideas of utopia such as the Garden of Eden, Shangri-la, Xanadu, and El Dorado, and a booming economy ranging from five-star hotels to inns, as well as restaurants and stores catering to their visitors, the island seems saturated. Now, its administrators are asking what the future might hold.

What would be a Capri 2.0 that would be more sustainable and less reliant on piped-in water, power, and money? How could the island develop a more creative and self-sufficient, as well as a more diverse, community? How could and should it build its heritage, both natural and human-made, in a responsible manner? What would be the implication of such projections for similar sites in Italy and beyond?

During a month-long workshop on the island, we developed a series of proposals, provocations, and experimental designs based on an analysis and documentation of the island, geology and geography, climate, history, and current social and physical landscape. Translated into drawings and images of considerable sweep and beauty, the speculations open up new possibilities for the island of Capri.

This project will form a part of the core of a book to be published to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the important Convegnio di Paesagio, which suggested ways in which not only Capri, but the Italian landscape as a whole could develop towards fostering creativity and craft while preserving and strengthening heritage. Similarly, this workshop will propose the applicability of its findings to larger landscapes.”

![]()

What would be a Capri 2.0 that would be more sustainable and less reliant on piped-in water, power, and money? How could the island develop a more creative and self-sufficient, as well as a more diverse, community? How could and should it build its heritage, both natural and human-made, in a responsible manner? What would be the implication of such projections for similar sites in Italy and beyond?

During a month-long workshop on the island, we developed a series of proposals, provocations, and experimental designs based on an analysis and documentation of the island, geology and geography, climate, history, and current social and physical landscape. Translated into drawings and images of considerable sweep and beauty, the speculations open up new possibilities for the island of Capri.

This project will form a part of the core of a book to be published to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the important Convegnio di Paesagio, which suggested ways in which not only Capri, but the Italian landscape as a whole could develop towards fostering creativity and craft while preserving and strengthening heritage. Similarly, this workshop will propose the applicability of its findings to larger landscapes.”

— Aaron Betsky, Book Proposal: Capri 2.0

Sponsored by the City of Capri, the workshop was intentionally framed outside the domains of sociological, economic, or scientific research, fields already extensively addressed by local governments and universities. Instead, we were asked to work with what has historically driven Capri’s development: the production of images that attract, evoke, and propose models of small-scale urbanism in which public space and agriculture are seamlessly embedded within winding streets and compact topographies.

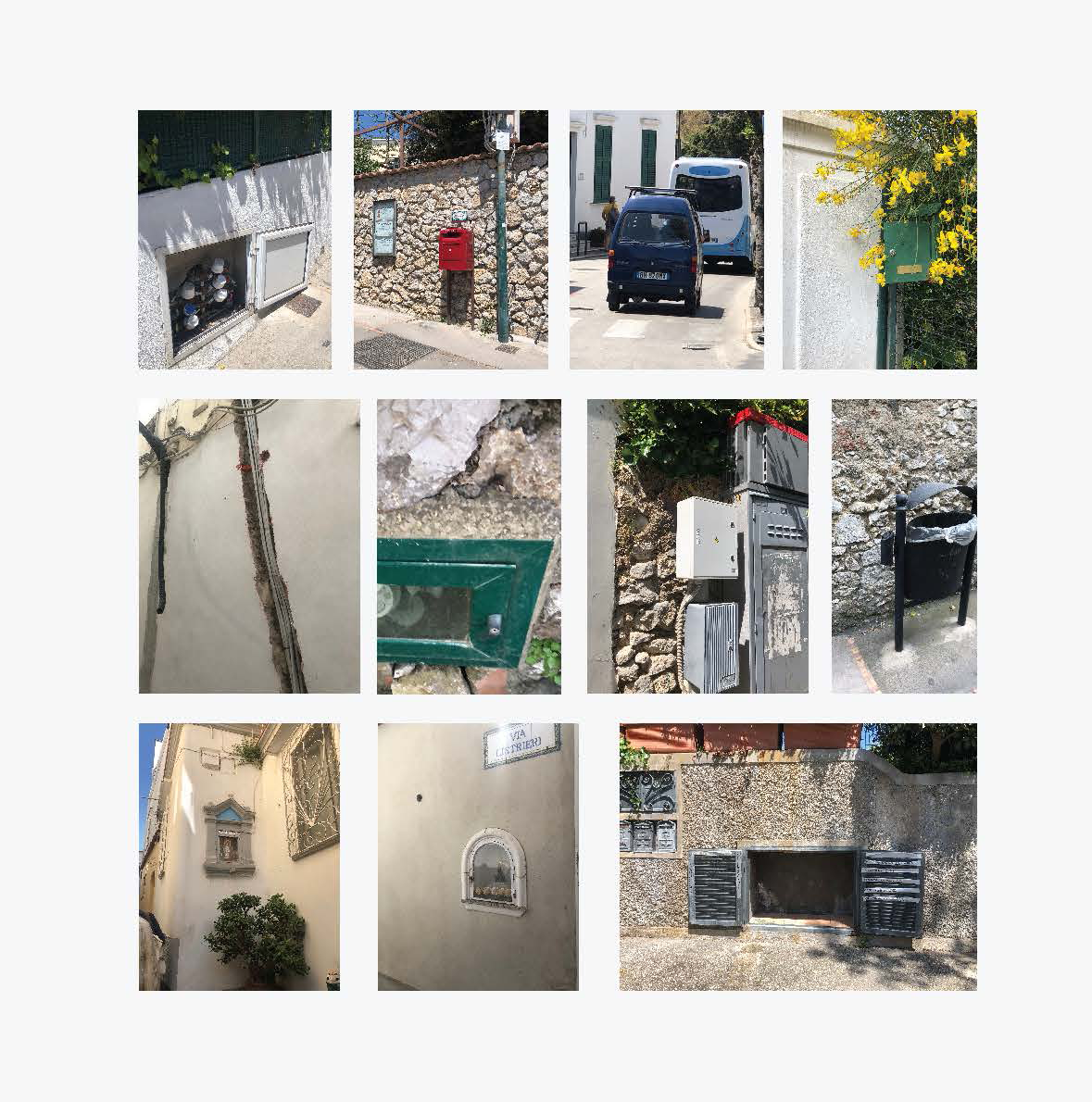

Capri’s urban form emerged from a condition of self-defense. As former Biennale President Paolo Baratta has observed, the island maintains a culture of concealment, of hiding in plain sight. Surfaces are immaculate and scenes carefully staged. What is celebrated is permanence. What is imported must negotiate an already permanent landscape, and what is introduced must either disappear or leave a lasting mark. Through successive historical transformations, the island’s landscape has continuously reformed itself, updating without erasing.

Landscape is commonly understood as the geophysical substrate of territory, including mountains, slopes, water, and vegetation. Capri, however, operates through a more constrained yet highly modified geological condition. Thick stone walls are rooted into the earth, oversized pottery is cemented onto rooftops, benches are carved directly from the ground, and flowers, wires, and infrastructural traces are etched into Roman stone. The island’s landscape is inseparable from layers of human intervention accumulated across eras. Walls, roads, gardens, infrastructure, and architecture form a single cultural and geological composite.

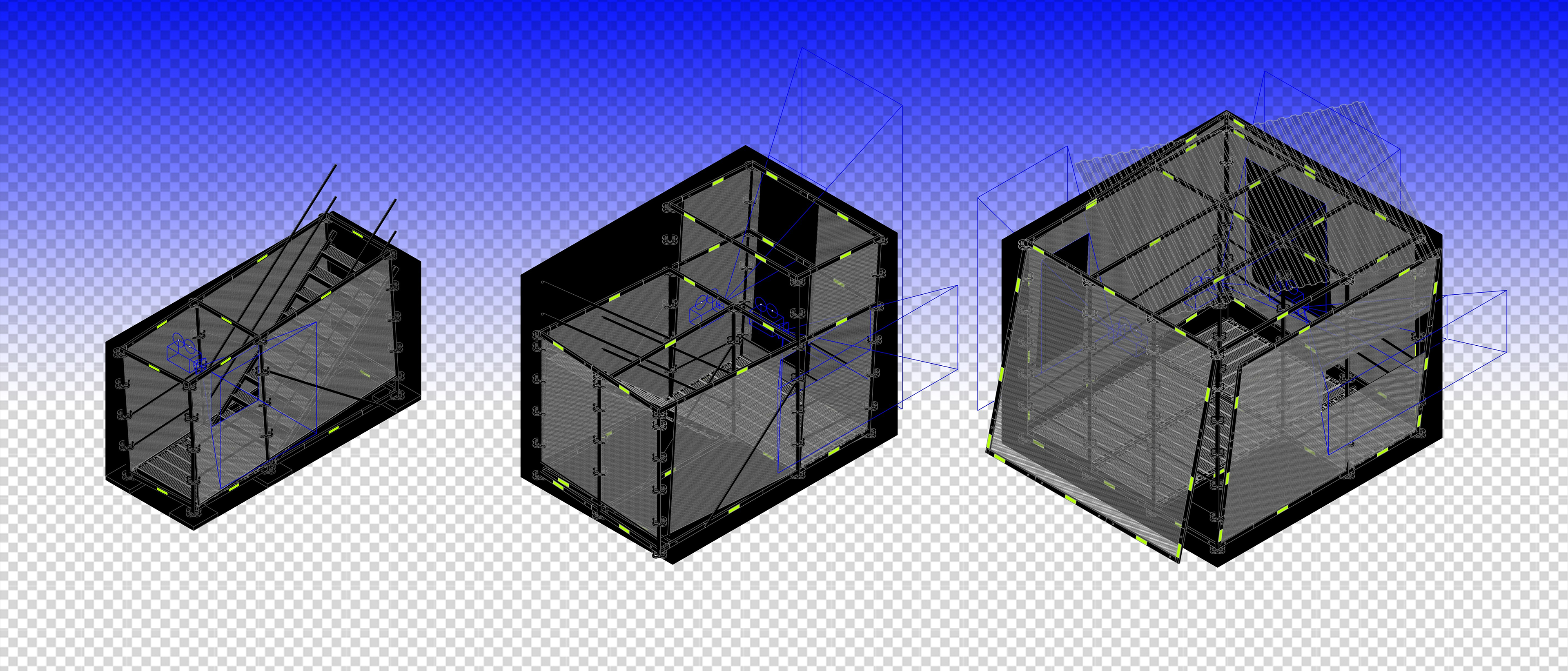

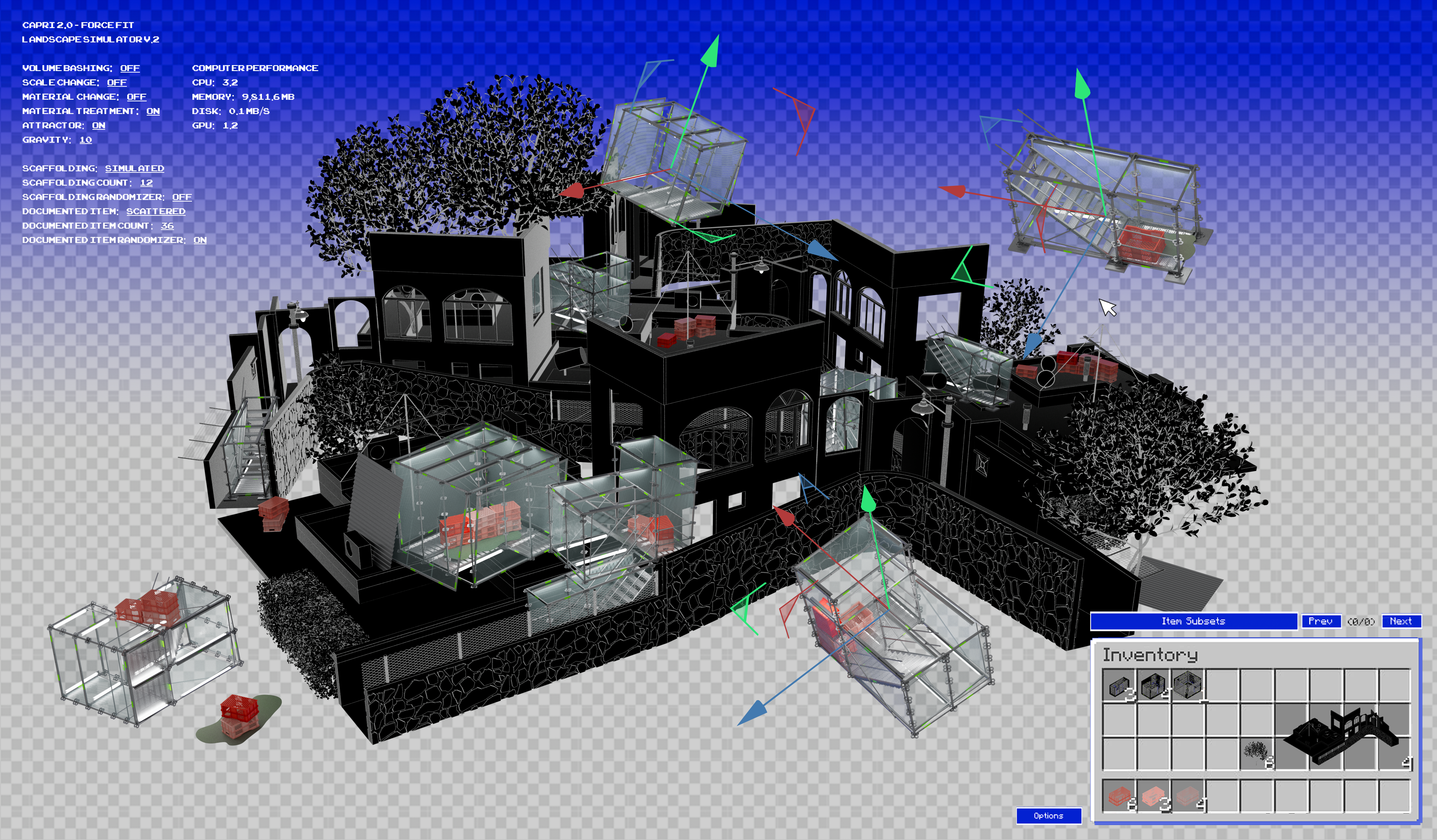

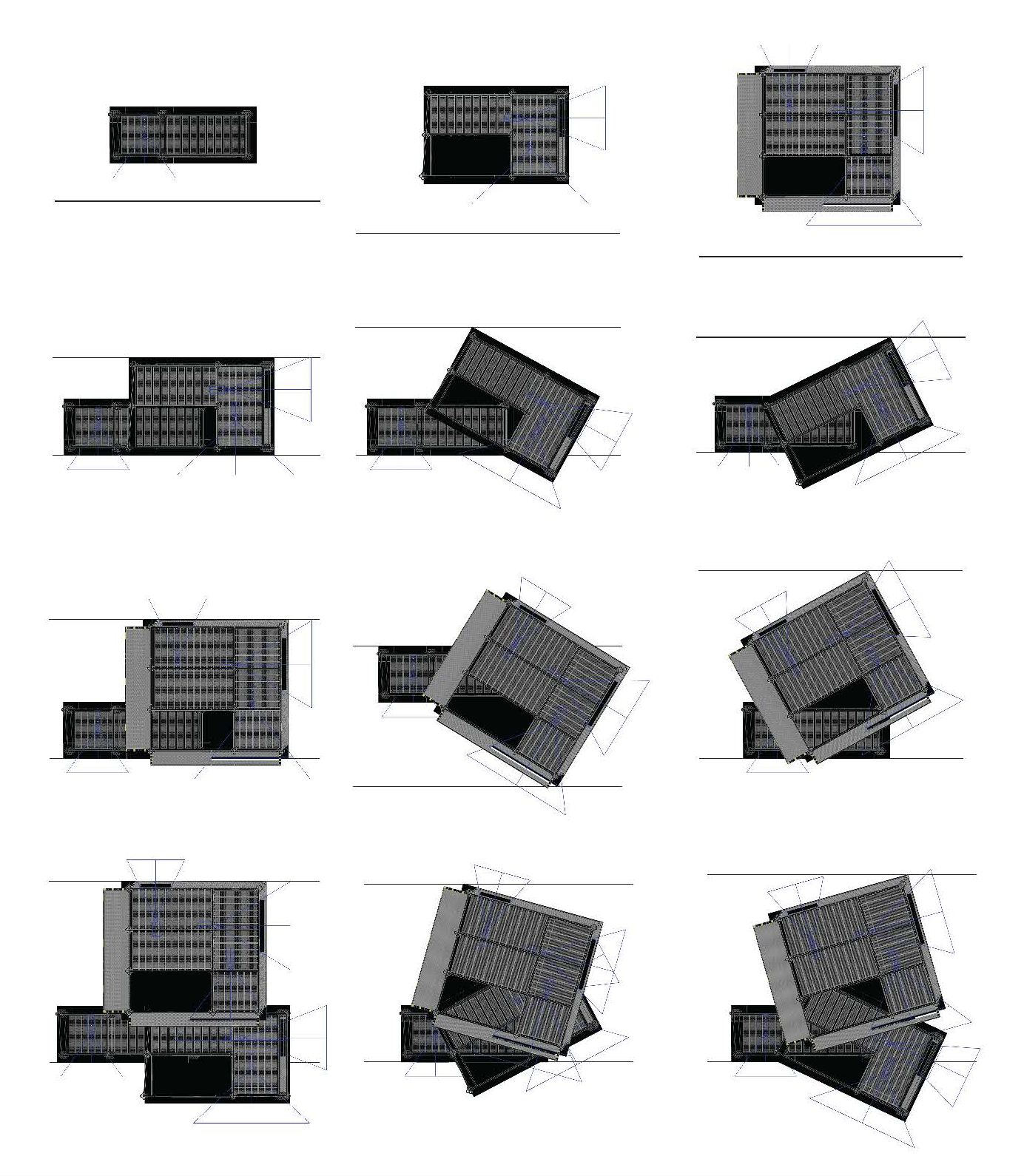

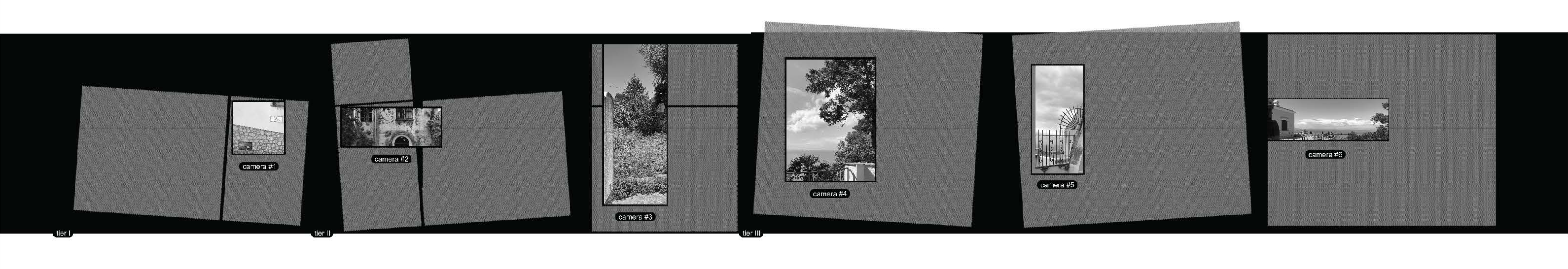

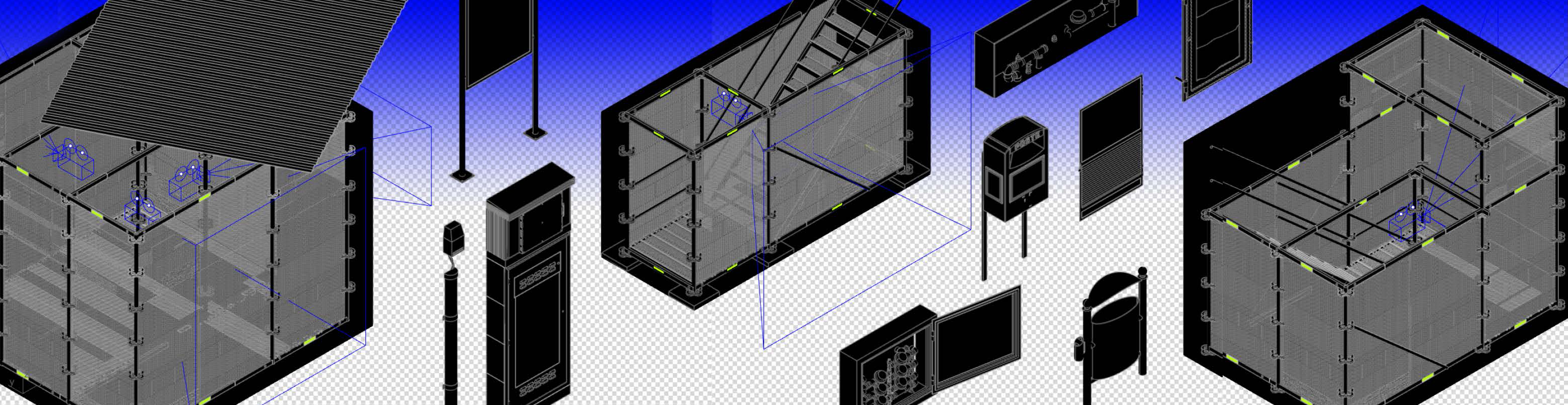

This project proposes an alternative reading of Capri’s historical landscape as a layered geomorphological canvas. The interactive framework, titled Force Fit, unfolds as a game. Participants first construct a digital simulacrum of a Capri-like landscape by assembling pre-made landscape modules into a single volumetric composition. Each module embodies a distinct spatial condition of the island, including narrow streets, sharp turns, stone garden walls, rooftops, and residential façades.

A set of camera cubes is then distributed throughout the assembled landscape. These cubes represent the transient viewpoints that characterize Capri today as a perpetually evolving tourist destination. Onto these mobile perspectives, the contextual intelligence of permanent residents is digitally upcycled and remapped as material assemblages, including steel awnings, scaffolding, fish nets, and construction debris. These elements function as mediators, tempering the pressures of change that might otherwise destabilize the island’s carefully layered continuity.

The placement of these upcycled materials is governed by simulated physics. Elements cannot overlap, scale arbitrarily, or float freely. Instead, they are force-fitted to the existing terrain, accumulating along contours and surfaces dictated by the landscape itself.

Through this process, transient perspectives solidify into a new spatial stratum that exists above, within, and around the existing terrain. The aim of Force Fit is to imagine a condition in which impermanent elements and materials, much like the contemporary cultural dynamics they embody, become inhabitable public spaces. These spaces do not overwrite history. Rather, they curate new ways of seeing Capri as simultaneously historical and contemporary, fixed and continuously becoming.

A set of camera cubes is then distributed throughout the assembled landscape. These cubes represent the transient viewpoints that characterize Capri today as a perpetually evolving tourist destination. Onto these mobile perspectives, the contextual intelligence of permanent residents is digitally upcycled and remapped as material assemblages, including steel awnings, scaffolding, fish nets, and construction debris. These elements function as mediators, tempering the pressures of change that might otherwise destabilize the island’s carefully layered continuity.

The placement of these upcycled materials is governed by simulated physics. Elements cannot overlap, scale arbitrarily, or float freely. Instead, they are force-fitted to the existing terrain, accumulating along contours and surfaces dictated by the landscape itself.

Through this process, transient perspectives solidify into a new spatial stratum that exists above, within, and around the existing terrain. The aim of Force Fit is to imagine a condition in which impermanent elements and materials, much like the contemporary cultural dynamics they embody, become inhabitable public spaces. These spaces do not overwrite history. Rather, they curate new ways of seeing Capri as simultaneously historical and contemporary, fixed and continuously becoming.